Areas

Overview

Areas are how we represent space in the world. We can split any map or space into areas that the characters can move between using grids, hex-grids, labels, lines, or any markers that help to distinguish between different sections of a space.

Vaguely defining areas allows some flexibility in how we split up a space. We can separate a space into pieces that conform to that space, rather than having to design our map to neatly fit into a grid. We can describe the map and character movement to fit the narrative and we don’t need to keep track of how many feet away each enemy is from each character.

Character Movement in Areas

Character movement is based on Movement Skills.

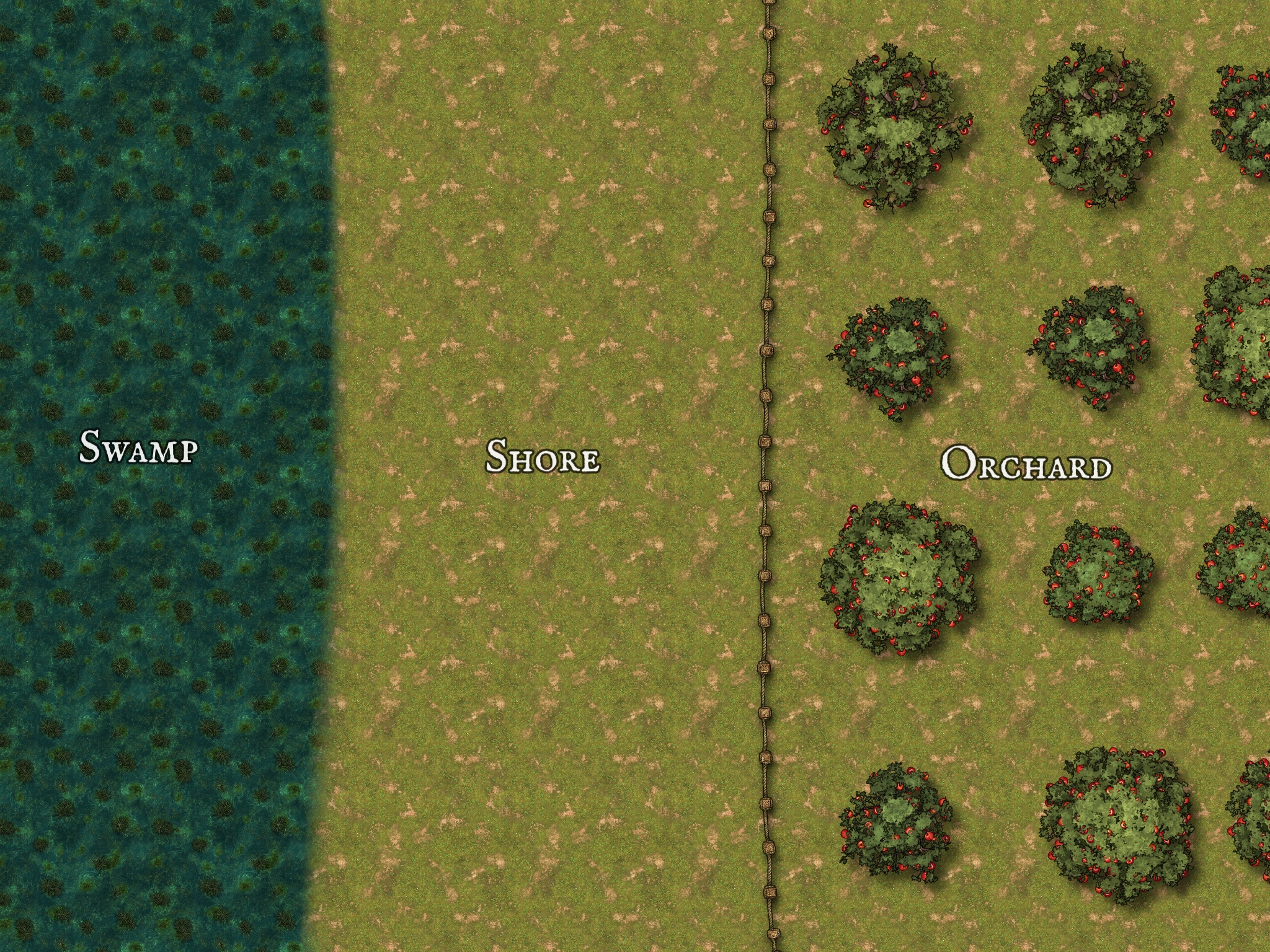

Consider the simple map below with 3 areas: the Swamp, Shore, and Orchard.

Imagine a character in the Orchard with Novice rank in the Running Skill who can use the Standard Run action.

If the character wants to move to the Shore, that character can spend 1 Action Point to perform the Standard Run action and move from the Orchard to the Shore, because the Shore is 1 area away from the Orchard.

When a character wants to move to a new area, they are considered to be moving out of their current area. This means that a character’s movement actions are affected by their current area, not the area they are moving into. We represent any Area effects by applying Conditions to a character after they move into an area.

Imagine that the narrator wants the Swamp to be an area that slows down the players. When the narrator describes this map, they can choose to tell the players directly that moving into the Swamp will apply the Slowed condition to their characters, or the narrator could describe the Swamp as having thick mud and tangled vegetation, and leave it to the players to figure out if it will slow them down.

If a character moves from the Shore to the Swamp, that Movement Skill action will take the normal Action Cost. After moving into the Swamp, they will be affected with the Slowed condition.

Then, if the character wants to move from the Swamp to the Shore, their Movement Skill action will be affected by the Slowed condition.

| Slowed | Movement Skill Action Cost is doubled. |

Using Areas for Combat

As a starting point, imagine each area in a combat map to be vaguely 20-60 feet wide. Consider what sections of the map naturally feel like different places, such as the different rooms and hallways of a building, and then imagine how the players will move through the space. Pretend you are describing the scene and think about how you would verbally differentiate the sections of your map.

If you are primarily using this space for combat, then it may be a good idea to define areas of the map based on how the players will strategically approach the situation. Or, perhaps you want the players to investigate a location for clues or make their way past a series of traps. Keep in mind what your players will be doing in this space as you break it up into different areas.

Combat Range in Areas

Combat action range limitations are described with areas as a unit of measurement. When running a combat with areas, we allow our players to make melee attacks on enemies in the same area without worrying about the details of movement. When a player says “I want to attack this enemy”, it is understood that their character will move to enable that attack to happen.

If there is a specific factor preventing the player’s movement within an area, the narrator and player can decide how to proceed. For example, if the player’s character is tied up, perhaps the player needs to use their turn to perform a skill check to free themselves. If there are spikes on the ground in the area, perhaps the character can move through the area, but will need to make a skill check when they attack to determine if they step on a spike and take damage.

Similar to melee weapon attacks, when a player wants to use a ranged weapon or combat action, there is mutual understanding that the player’s character can move within its current area, and that enemies are generally existing within the entirety of their area. If we imagine a bow to have a range of 60 feet and our areas to be vaguely 20-60 feet wide, we can imagine that during the player’s turn, it was possible for their character to move within 60 feet of the enemy before attacking.

Weapon Range Limit Examples

| Weapon | Range |

|---|---|

| Melee Weapons | Within the same area |

| Sling | 1 area away |

| Crossbow | 2 areas away |

| Bow | 2 areas away |

| Longbow | 3 areas away |

The narrator and player should work together to determine if the player’s character can reasonably see an enemy from their area, or if there are any factors hindering the player’s ability to attack an enemy. Here are some examples with suggested penalties. The narrator should use their own judgement to adjust these to fit the situation or their preference.

| Situation | Penalty |

|---|---|

| Character has no line of sight to enemy | Character cannot attack the enemy |

| Character’s feet are restrained | Character has an Attack Modifier of -2 |

| Enemy partially hiding behind cover | Enemy has a Defense Modifier of +2 |

| Enemy is in a shield wall formation with other enemies | Enemy has a Defense Modifier of +3 |

| Combat takes place during an intense storm | Attack Modifier of -1 for melee attacks Attack Modifier of -3 for ranged attacks |

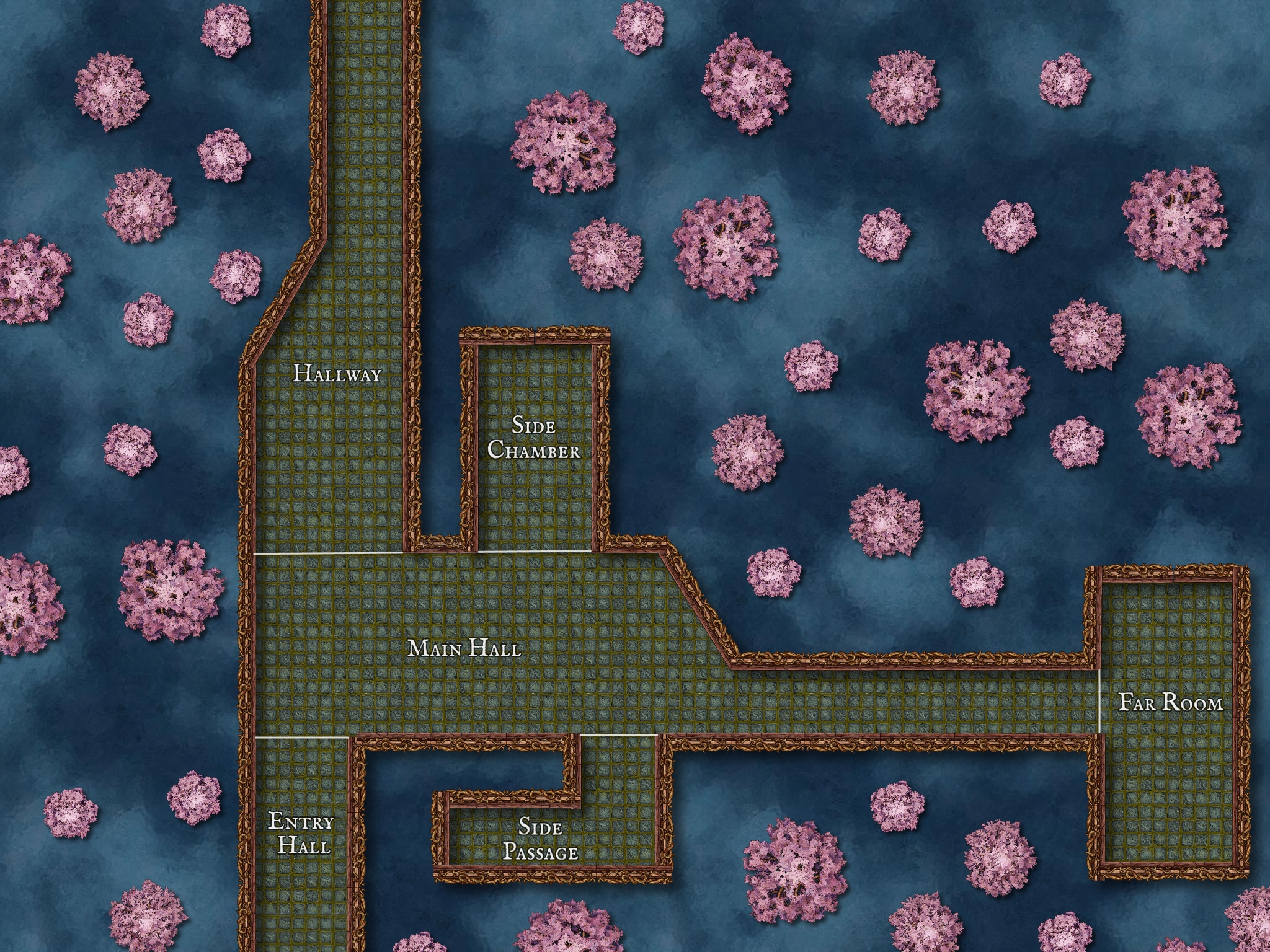

Here is a combat map, with line of sight examples listed below.

- A player in the Hallway cannot see an enemy in the Side Chamber.

- A player in the Main Hall can attack an enemy in the Side Chamber with an appropriate ranged weapon. There is no place in the side chamber that the enemy can hide where they cannot be seen by the player in the Main Hall.

- A player in the Main Hall might be able to see an enemy in the Side Passage. If a player wants to attack an enemy in the Side Passage, the narrator should communicate if the enemy is trying to hide or is confronting the player. If the enemy is hiding, they might be at the very end of the Side Passage and the player will need to move into the area to be able to see them. If the enemy is confronting the player, they may be standing at the entrance to the side passage and can be seen from the Main Hall.

Keep in mind that the narrator could divide this same map into different areas that more closely represent the walls of these rooms, such that line of sight would be easier to talk about and keep track of. The narrator should consider the playstyle of the players in their group when deciding how to divide a space.

For players that want a more detailed or strategic combat scenario, it could be a good idea to make a more detailed map that provides strategic options for your players. Also consider options for strategy that are not based on movement speed or distance. Add environmental hazards, hiding spots, defensive locations, very brightly lit or poorly lit areas, or other thematically appropriate features to your map. Then, the narrator can decide (on their own or with the players) what bonuses or penalties seem fair for those map features.

We do lose a lot of strategic complexity by making our positioning a more vague, but our style of game is narratively-focused and we can increase the pacing of combat by simplifying player decision-making regarding movement.

However, if you and your players want a more strategic fight, you can use a traditional grid/hex map. Define an area to be 30 feet and convert any areas measurements to a measurement in feet.

Below is an example of the above Weapons table and the Running skill table using feet instead of areas. Keep in mind that these are just approximations - if a narrator and players feel like a longbow should have more range than 90 feet, then increase it to match what feels right.

Weapons (measured in feet)

| Weapon | Range |

|---|---|

| Melee Weapons | In an adjacent tile |

| Sling | 30 feet |

| Crossbow | 60 feet |

| Bow | 60 feet |

| Longbow | 90 feet |

The generic formula for determining rate of movement in feet is:

Measurement in Feet = (Measurement in Areas * 30) / Action Cost

Running

| Title | Description | Rank | Action Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untrained Run Speed | 15 feet | Untrained | 1 |

| Standard Run Speed | 30 feet | Novice | 1 |

| Improved Run Speed | Flavorful skill | Adept | 1 |

| Expert Runner | 60 feet | Expert | 1 |

High Ground Advantage

We define High Ground as being positioned approximately 5 feet higher than the adjacent ground. It represents a relative distance where two characters can still interact, but their interaction is affected by the height difference. The specific distance is not important

In combat, when a character is positioned on higher ground than another opposing character, they are in an advantageous position.

When a character is on relative High Ground compared to another character and performs an Attacking Skill Roll against that character, they add an Attack Modifier of +2 to the Attacking Skill Roll.

Consider the below example where the narrator describes the space and High Ground is used to the player’s advantage.

Narrator: You enter the dining hall. A large crystal chandelier illuminates a long, sturdy table piled high with a sumptious autumn feast. At the far end of the room, the chieftain of the bandits sits at the head of the table, gorging himself on the delicious food. Against the wall, the family you have been tasked with rescuing sits on the floor with their hands and feet tied together.

Player: Can I jump on the dining table?

Narrator: Of course! Do you say anything as you leap onto the table?

Player: Hmm, I feel like my character would be completely focused on saving the family as quickly as possible, and wouldn’t pause to say anything. I’d like to run straight at the bandit chieftain and attack him with my sword.

Narrator: Makes sense! You sprint up the table, stepping over loaves of fresh bread, vegetable casseroles, and large clay pots of steaming soup. You reach the head of the table and swing your sword down at the bandit chieftain!

Player: Let’s see… I think I’ll use the Standard Attack action.

Narrator: Alright, since you’re standing on the table above the bandit, your character has the advantage of high ground.

Player: Okay, my character has the Novice rank in One-Handed Weapons so I’ll roll 1d6… I rolled a 4!

Narrator: Remember to add +2 because of the high ground advantage.

Player: Oh, right - so my total result is 6.

Narrator: The bandit chieftain has the Adept rank in One-Handed Weapons, so he’ll roll 2d6 to defend himself… he rolled 5! You thrust your blade past his axe handle and stab him in the shoulder.

Player: The Hit Result is 1, plus my sword’s Damage Bonus of +1, so I do 2 damage!

Narrator: The chieftain isn’t wearing armor, and he has no other Damage Reductions, so he takes 2 damage! He clutches at his shoulder and stumbles back from the table.

Using Areas for Travel

Travel between locations on a world map can be approximated by the narrator. It can be helpful to first choose two locations and decide how long it would take the players to travel from one to the other. Then, use that distance as a reference when approximating travel time between other locations on the map.

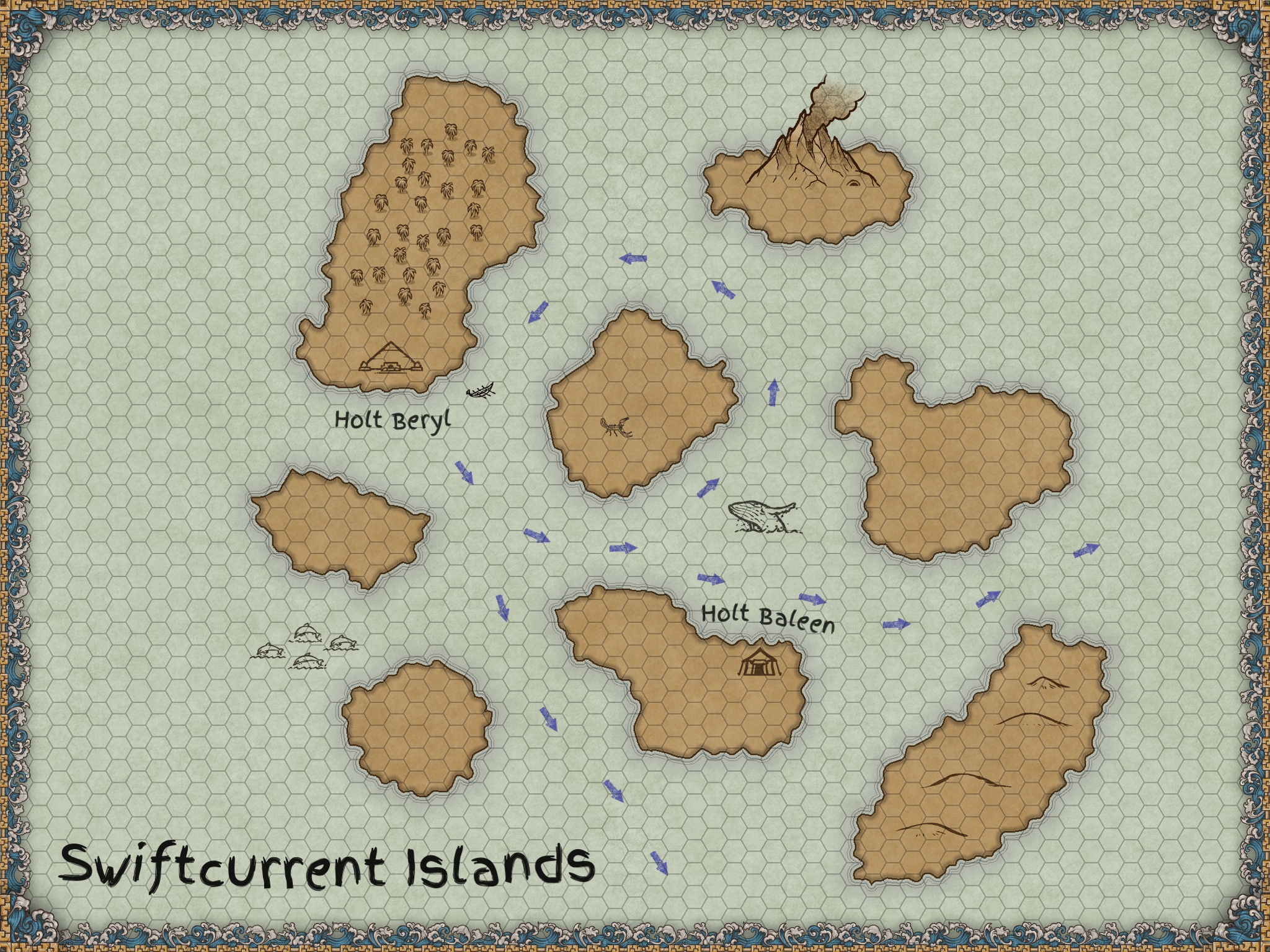

Here is a regional map with distance examples below.

| Starting Location | Destination | Travel Time (by foot) |

|---|---|---|

| Sunflower Meadow | Green River Enclave | 7 days |

| Sunflower Meadow | The Blustery Plains | 4 days |

| Sunflower Meadow | Thick-Thistle Marches | 7 days |

| Sunflower Meadow | The South Sands | 10 days |

| Green River Enclave | The South Sands | 14 days |

My “reference distance” was the distance between Sunflower Meadow and Green River Enclave.

It can be helpful to first measure based on the most common form of travel for your players. If they are temporarily traveling in a different method, such as by boat, imagine how much faster that method of travel is than walking. Consider, for the boat example, if they are traveling with or against the current or if the wind is favorable. Try to describe to your players some of the factors affecting their travel, even if the travel will be mostly skipped over. Below is an example of distance for players traveling along the Green River between the two towns on the map.

| Starting Location | Destination | Travel Time (by canoe) |

|---|---|---|

| Sunflower Meadow | Green River Enclave | 2 days |

| Green River Enclave | Sunflower Meadow | 4 days |

In this example, we take into account that the current is running towards the ocean. Imagine how fast the current is in the river and adjust the travel time to what feels right.

Sometimes travel can be a factor that creates narrative situations for your players. You can guide them towards interesting or notable locations while still giving your players the freedom to explore the map. By defining some mechanics behind player travel, you can give players the opportunity to make decisions that feel impactful and provide some flavor to moving around the map. It can help give a memorable or unique feeling to a certain area of your world or an arc of your story.

As the narrator, you can use environmental factors to gently guide your players, indicating to them “Hey, there is something cool over here that I’ve prepared for you to enjoy” and letting them choose to engage with it, rather than having them feel forced down a pre-determined path.

Having some simple mechanics behind traveling can also give the narrator a layer to obscure their influence on the direction the story will take. The most important goal is for the players at the table to have fun, and it’s helpful for the narrator to be able to exert some guidance over the story so they can create a fun and satisfying experience for the players.

You can apply a square or hexagonal grid to a map, like in the below example.

In this case, I added blue arrows to represent the ocean currents. My players acquired a small boat in Holt Beryl and I wanted them to explore the unmarked areas of the map, even though they didn’t have a narrative reason to do so. I let the players choose between a rowboat and a sailboat (either way the current becomes a factor) and I can provide a penalty for traveling against the current. If the players choose to travel against the current, we can create some narrative situation out of that, and the players’ decision will make a difference in how the story unfolds. If the players follow the current, they’ll pass by the big volcano island and I can present it as an interesting location to explore. Either way, the story has changed because of the player’s decisions about travel.

Physical exhaustion can also be a factor that creates decisions for the players that can change or create narrative. A grid to represent distance helps focus on a mechanic like physical exertion by representing distance more specifically. Do your best to imagine what kind of decisions your players will enjoy and invent factors that create those types of decisions.